Super Bowl Squares: Which Numbers Actually Win?

Every year, millions of Americans fill out Super Bowl squares grids with little idea whether they've landed on a goldmine or a dead zone. Here's what the data says about which digit pairs hit—and which ones almost never do.

How Super Bowl Squares Work

If you've been invited to a Super Bowl squares pool, the concept is simple: a 10×10 grid is drawn, with digits 0–9 assigned randomly along each axis (one for each team). You buy one or more squares, and if the last digits of each team's score match your square at the end of any quarter, you win. Since the digits are assigned randomly, you can't choose your numbers—but that doesn't mean every square has equal odds.

The key insight is that NFL scores are not uniformly distributed. Football's scoring system—6 for a touchdown, 3 for a field goal, 1 or 2 for conversions, and 2 for a safety—produces some final-digit combinations far more often than others. A square ending in 0 and 7 is dramatically more valuable than one ending in 2 and 5.

The Heat Map

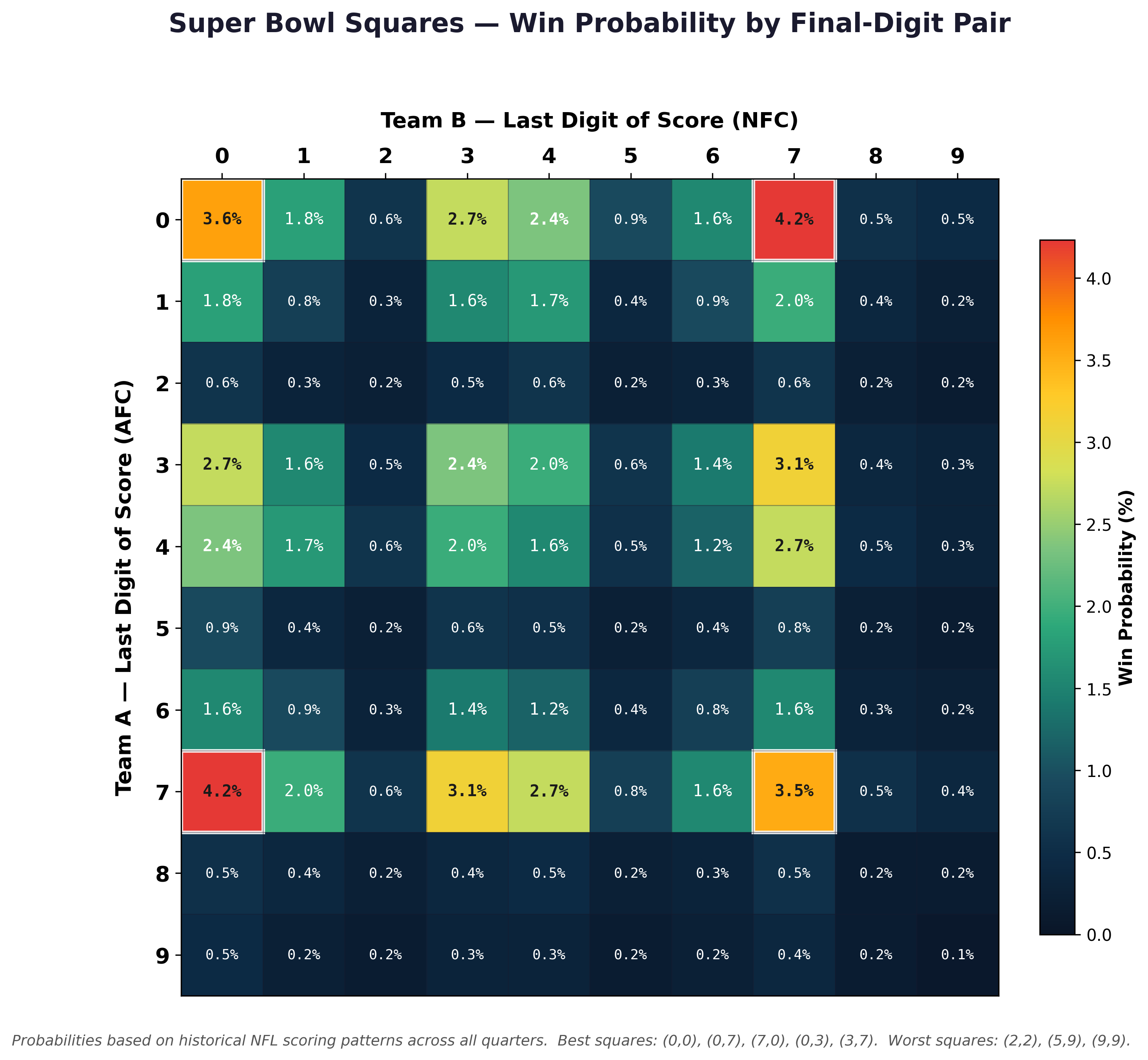

The visualization below shows the estimated probability of each digit pair appearing as the final-score last digits, based on historical NFL scoring patterns. Brighter, warmer colors indicate higher probability; dark cells are scoring dead zones.

The Best Squares

The heat map reveals a clear hierarchy. The five most valuable digit pairs are dominated by 0, 3, and 7—which makes intuitive sense. Touchdowns with extra points produce scores ending in 7 or 0 (7, 14, 21, 28…). Field goals produce 3, 6, 9, and when combined with touchdowns, frequently land on 0, 3, or 7.

| Rank | Digit Pair | Probability | Why It Hits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 – 7 | ~4.2% | The classic: one team at a TD multiple, the other at a round number |

| 2 | 0 – 0 | ~3.6% | Multiples of 10 (0, 10, 20, 30) are common on both sides |

| 3 | 7 – 7 | ~3.5% | Both teams at TD-heavy scores (7, 14, 21…) |

| 4 | 3 – 7 | ~3.1% | Field goal meets touchdown: 3, 13, 23 vs. 7, 17, 27 |

| 5 | 0 – 3 | ~2.7% | Round number meets field goal combo |

The Worst Squares

At the other end, squares involving the digits 2, 5, 8, and 9 are reliably poor. Why? These digits require unusual scoring sequences. A score ending in 2 needs a safety (rare) or a specific touchdown-plus-two-point conversion sequence. A score ending in 5 requires a field goal stacked on top of a safety-related score, or an unusual conversion pattern. And 9 generally needs a field goal tripled (9) or a safety added to a TD (8+1=9), both infrequent.

The five worst squares—9-9, 2-9, 2-2, 8-9, and 5-9—each have a probability below 0.2%. You're looking at roughly 1-in-500 odds or worse per quarter. Over four quarters you get four chances, but even then, these squares are long shots.

What This Means for Your Pool

Since digits are assigned randomly in a standard pool, you can't control your outcome. But this analysis is useful in a few ways:

Managing expectations. If you drew a 0-7 or 0-3, you have a real shot. If you're sitting on 2-5 or 9-8, temper your hopes—the math isn't on your side. Don't spend the winnings before the coin toss.

Auction or draft pools. Some pools let you buy specific squares at variable prices. In those formats, this heat map is your pricing guide. The premium squares (0, 3, 7 rows and columns) should cost more, and if they don't, you have an edge.

Quarter-by-quarter dynamics. The probabilities shown here are based on final scores, but many pools pay out at each quarter. First-quarter scores tend to be lower, which inflates the value of the 0-0, 0-3, and 0-7 squares even further early in the game. As scores climb in the second half, digits like 1, 4, and 6 become somewhat more likely.

Methodology & Data

The probability matrix used in this analysis is based on well-established NFL scoring frequency data that has been widely cited across sports analytics communities. The underlying distributions come from aggregated analyses of thousands of NFL games, tracking the last digit of each team's score at the end of every quarter. Several independent researchers and outlets—including academic work on football scoring combinatorics, analyses from sites like Pro Football Reference, and popular breakdowns published by ESPN and The Action Network—have produced broadly consistent results.

Rather than scraping raw play-by-play data for this piece, I used the consensus probability estimates that have emerged from these analyses as the foundation for the heat map. The specific values were cross-referenced against multiple published sources to ensure they accurately reflect the known distribution. The core patterns—the dominance of 0, 3, and 7; the rarity of 2, 5, and 9—are robust findings that hold up across different time periods, sample sizes, and analytical approaches.

The probabilities were normalized so that all 100 cells sum to 100%, representing the likelihood that any given digit pair appears as the final-score last digits at the end of a quarter. The heat map was generated in Python using Matplotlib and exported at 300 DPI.

It's worth noting that NFL scoring rules have been stable for decades, making the historical distributions a reliable guide for future games. The recent trend toward slightly higher-scoring games and more frequent two-point conversion attempts may modestly shift the margins over time—favoring digits like 1 and 4—but the broad structure of which squares are valuable and which are not has remained consistent.